Rare Earth (dir. Elizabeth Knafo, 54min, 2014) explores the re-opening of an historically toxic rare earth mine in the California desert, and the intensifying land rush for these high-tech minerals across the world.

::: To order an educational or screeing link please email eliaolik {at} gmail {dot} com :::

From the Mojave desert, to the Pacific seabed, to the surface of the moon, the rush for rare earth minerals is afoot.

From the Mojave desert, to the Pacific seabed, to the surface of the moon, the rush for rare earth minerals is afoot. The film is a portrait of changing desert landscapes and the residents who grapple with the impacts of industrial mining. Rare Earth traces the toxic and transformative legacy of treasure hunting in the American West — a legacy of speculation, produced scarcity and the social violence of resource extraction—deepening in our era of global climate change.

* -------- *

*

“The film is a poem in image and sound of place, a particular place: the Mojave desert, but also a place called ‘the desert’”

—

Mazen Labban, Rutgers University

“[A] film to really focus our attention on the material underpinnings of modern life.”

—

-Matthew HimleyUniversity of Illinois

* -------- *

* --------

*

EXCERPTS FROM

Details from the Rare Earth Frontier

Originally published in Cabinet magazine, 2017

download the pdf

Details from the Rare Earth Frontier

Originally published in Cabinet magazine, 2017

download the pdf

* -------- *

*

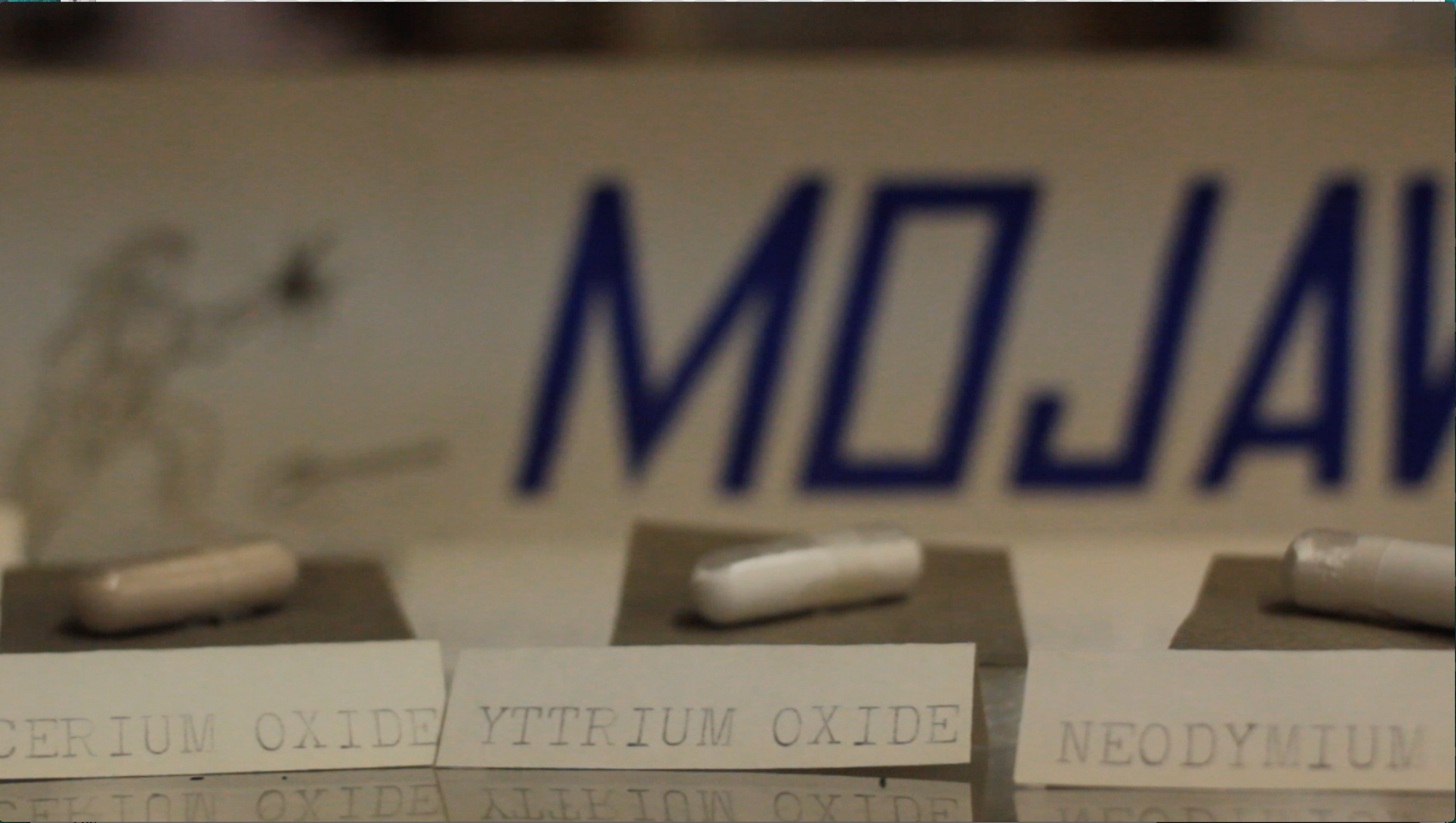

At a place called Mountain Pass in the Mojave Desert, just outside California’s Mojave National Preserve, is a recently bankrupt rare earth mine and processing plant. There are seventeen rare earth elements, which are divided into “heavies” and “lights” based on their relative atomic weights. The heavies are crucial components in consumer electronics and military technology, in the physical infrastructure and digital capabilities of the internet, and in surveillance tools. They are used in the computing, display, and maintenance of systems of global trade, digital warfare, and militarized policing, as well as in the storage servers where social media sites and digital surveillance data are warehoused. Heavy rare earths, which Molycorp, Inc., the company that owned the mine in California, was hoping to extract, are, at this time, irreplaceable ingredients in all things digital. Light rare earths, on the other hand, are used in more mundane industrial applications, such as uv window coatings and petroleum production.

The rare earth mine had been in operation for fifty years, but was closed in 2002 by environmental regulatory agencies. The operation was reopened and expanded in 2010; the project was dubbed “Project Phoenix,” presumably in reference to the resurrection of the mine. (At the time of its 2002 closure, the operation had in fact been owned by another company of the same name; the newly formed company behind the 2010 reopening purchased the name and the site in 2008.)

At the groundbreaking ceremony, Molycorp emphasized “green” energy and national security as their rationales for beginning to mine again. Those speaking on behalf of the company touted the uses of rare earths in wind turbines and electric cars, and asserted that the mine would help make the United States independent of China’s rare earth supply. (Over

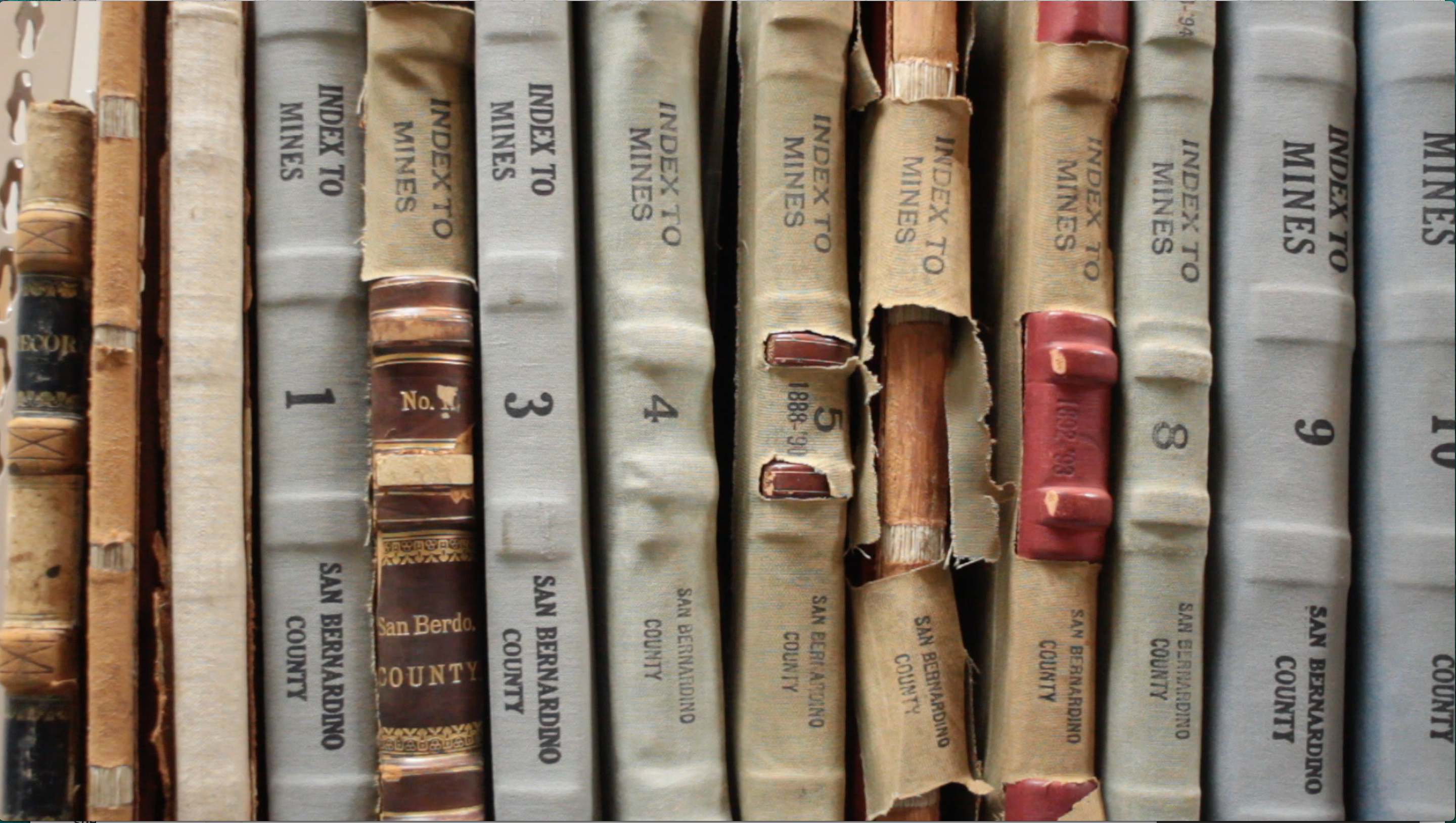

90 percent of the rare earths on the world market comes from Chinese mines). Neither Molycorp nor the politicians at the event made any mention of the radioactive waste generated in rare earth processing. Nor did they mention the fact that in 1986, the company town at Mountain Pass closed down after workers and their families started to get sick. There is a dearth of public information on what effect the radioactive dust plaguing the mine’s surroundings had on the town’s closure, and what effect it has on the area to this day. For their part, the mine’s management claimed that the cost of running the town became prohibitive once the mine’s profits began to fall, in part due to a federal government decision to make unleaded gasoline—the production of which did not require a particular rare earth mined at the site—the official standard in the United States. Soon after the reopening, metal poles started to dot the hills surrounding the pit as the company began staking new mineral claims in search of additional deposits, especially those containing higher concentrations of lucrative heavy rare earths. Such claims are part of a legal framework—originating in the late nineteenth century and fundamental to white advancement into the western parts of the continent—that introduces public land into the marketplace by allowing industrial mining concerns to lease or even purchase that land if they can prove it has mineral value. The land and mineral claims surrounding Molycorp’s pit mine are examples of how us frontier narratives and economics are accompanied by a supporting bureaucracy designed to push the us project westward. These extractive enterprises, premised on racial hierarchies and land dispossession, operate to produce, and then exploit, rarity—an outlook that helps make the very possibility of human life on earth increasingly rare. The project presented here revisits material from a documentary I made between 2011 and 2014 that examined the way in which the Mountain Pass mine has permanently altered the desert by depositing its radioactive waste there. This work considers the “rare earth frontier”—a term I have borrowed from Boston University professor Julie Klinger—the parameters of which are industrial in pace, ubiquitous in terms of technological application, and global, even extraterrestrial, in scale. To grasp the scope of the United States’ fundamental relationship to geology, it is important to remember that pressure on rock is always also pressure on the softer, more permeable, forms of life—humans, plants, animals. These enterprises, European-colonial at first, and later a collaboration between the state and corporate interests, formed the basis for the settlement of the country and rely on the commandeering of natural resources and the use of exploited labor, both on the land and hundreds of feet below it. A geologist described the global media and investment frenzy of 2010 surrounding rare earth prospecting and mining as “rare earth fever.” This allusion to gold fever, and the California gold rush of 1848, connects geology to the notion of the frontier and the ways in which it has functioned as a premise for transforming spaces, conceptual or physical, into sites of extractive, capitalist production. The frontier sits adjacent to the current territory, territory being distinct from terrain in that it serves as the marker of colonial, racial, economic, and cultural rule.

The rare earth mine had been in operation for fifty years, but was closed in 2002 by environmental regulatory agencies. The operation was reopened and expanded in 2010; the project was dubbed “Project Phoenix,” presumably in reference to the resurrection of the mine. (At the time of its 2002 closure, the operation had in fact been owned by another company of the same name; the newly formed company behind the 2010 reopening purchased the name and the site in 2008.)

At the groundbreaking ceremony, Molycorp emphasized “green” energy and national security as their rationales for beginning to mine again. Those speaking on behalf of the company touted the uses of rare earths in wind turbines and electric cars, and asserted that the mine would help make the United States independent of China’s rare earth supply. (Over

90 percent of the rare earths on the world market comes from Chinese mines). Neither Molycorp nor the politicians at the event made any mention of the radioactive waste generated in rare earth processing. Nor did they mention the fact that in 1986, the company town at Mountain Pass closed down after workers and their families started to get sick. There is a dearth of public information on what effect the radioactive dust plaguing the mine’s surroundings had on the town’s closure, and what effect it has on the area to this day. For their part, the mine’s management claimed that the cost of running the town became prohibitive once the mine’s profits began to fall, in part due to a federal government decision to make unleaded gasoline—the production of which did not require a particular rare earth mined at the site—the official standard in the United States. Soon after the reopening, metal poles started to dot the hills surrounding the pit as the company began staking new mineral claims in search of additional deposits, especially those containing higher concentrations of lucrative heavy rare earths. Such claims are part of a legal framework—originating in the late nineteenth century and fundamental to white advancement into the western parts of the continent—that introduces public land into the marketplace by allowing industrial mining concerns to lease or even purchase that land if they can prove it has mineral value. The land and mineral claims surrounding Molycorp’s pit mine are examples of how us frontier narratives and economics are accompanied by a supporting bureaucracy designed to push the us project westward. These extractive enterprises, premised on racial hierarchies and land dispossession, operate to produce, and then exploit, rarity—an outlook that helps make the very possibility of human life on earth increasingly rare. The project presented here revisits material from a documentary I made between 2011 and 2014 that examined the way in which the Mountain Pass mine has permanently altered the desert by depositing its radioactive waste there. This work considers the “rare earth frontier”—a term I have borrowed from Boston University professor Julie Klinger—the parameters of which are industrial in pace, ubiquitous in terms of technological application, and global, even extraterrestrial, in scale. To grasp the scope of the United States’ fundamental relationship to geology, it is important to remember that pressure on rock is always also pressure on the softer, more permeable, forms of life—humans, plants, animals. These enterprises, European-colonial at first, and later a collaboration between the state and corporate interests, formed the basis for the settlement of the country and rely on the commandeering of natural resources and the use of exploited labor, both on the land and hundreds of feet below it. A geologist described the global media and investment frenzy of 2010 surrounding rare earth prospecting and mining as “rare earth fever.” This allusion to gold fever, and the California gold rush of 1848, connects geology to the notion of the frontier and the ways in which it has functioned as a premise for transforming spaces, conceptual or physical, into sites of extractive, capitalist production. The frontier sits adjacent to the current territory, territory being distinct from terrain in that it serves as the marker of colonial, racial, economic, and cultural rule.

Scarcity of resources must be enforced in order to push settlers and investors to the frontier, where its resources are then transformed and subsumed into the economic system. Settlers, prospectors, and investors take the land; time and time again, they are the foot soldiers of the dispossession of the indigenous. Rather than being a previously undiscovered space, the frontier is a ground created through an orchestrated and projected emptiness, an assigned uselessness: a generative narrative that allows a privileged race and class to accumulate and circulate resources and capital at the expense of the people long establihed in these places.

This ideological narrative, formed during the colonial period, remains operative today in an economic context that propels us toward catastrophic global climate change under the inequities of racial capitalism. The rare earth frontier is the frontierism of our enduring neoliberal era, a time of increased police militarization, global surveillance, and increasingly extreme privatization and extraction. Though similar to the frontier mentality of the nineteenth century, the narrative now includes not only digital technology and weaponry but also an “end of-the-world” ideology that determines and sustains its form and method. It is distinctly post-9/11 in its particular paranoias and aspirations, yet it is also rooted in the visions of total surveillance from earlier epochs of American paranoia.

This projection of endless surveillance and war is a crucial component of what allows the supposed wasteland of the desert to be “recuperated” through continued investment. The Molycorp mine’s management had promised investors and local politicians that the minerals processed at Mountain Pass would facilitate the creation of equipment not only necessary for green technologies but also for the American military. But even though none of the rare earth elements for the manufacture of military equipment was actually in the ground at Mountain Pass, the “critical minerals” narrative worked long enough to raise millions of dollars in investments. In the Mojave Desert, the mining pits and shafts of the past centuries’ prospecting are scattered around the parklands and desert roads. Through the many eras of US history, mineral matter has been fundamental to the generation of power: social, ideological, militaristic, and energetic. With the incorporation of rare earth technologies, these powers course through the flicker of location services, data mines, and surveillance servers, through our screens as we watch ourselves and the state and its corporate affiliates find new ways to ensure their power by watching us back.

The Mountain Pass mine sits at the foot of Clark Mountain, which consists in part of rock more than a billion years old heaved up from deep beneath the earth’s surface as a result of the collision of the North American continent with the oceanic crust beneath the Pacific Ocean. The mountains and playas of this desert lay bare the planet’s elemental story—Earth’s four-billion-year-old creation visible in its seams, transitions, and uplifts of stone. And the landscape is abundant with minerals; limestone, basalt, granite, turquoise, zinc, tungsten, borax, lead, copper, silver, and gold are all present. The Indigenous peoples knew an overland route from the area around present-day Santa Fe to the Pacific Ocean that crossed through this part of the desert, but it eluded the Spanish until they learned of it from their Mojave guides. The survival of the Spanish missionaries and gold-seeking soldiers relied heavily on the knowledge that the Mojave, Serrano, Paiute, Chemehuevi, Hualapai, and Vanyume peoples shared with them. Gold was once mined beneath this mountain, as were copper, zinc, and lead when prices for those metals rose steeply during World War I. The US government classified this land as public land when it took control of it, but its later, industrial use was facilitated by provisions such as those in the 1872 General Mining Law, which were designed to encourage the expansionist programs of “manifest destiny” and the mining booms of the Gold Rush. These laws sanctioned the forcible and violent conversion of Native American lands into American territories, which was often achieved for the US government by proxy via the miners, homesteaders, and ranchers who raced west and tied their livelihoods to these contested lands. Often, though, before the miner or settler made it west, speculators had already laid claim to huge tracts of land, seizing it at cheap prices, often under different names, thereby skewing supply and demand and creating some of America’s first real-estate bubbles. In the 1940s, a Nevada prospector, inspired by a government newsreel entreating citizens to seek uranium, took his Geiger counter out to an area around the abandoned gold mine at Clark Mountain, where he located a radioactive vein. What the prospector found wasn’t uranium, but a deposit of radioactive host rock containing one or more of the seventeen rare earth elements. Shortly after the Molybdenum Corporation of America (later renamed Molycorp) opened a mine there in 1952, two rare earth elements were found: europium and yttrium, both of which are necessary to create a bright red phosphor used in color television cathode tubes. The mine’s management claimed that every color tv in the United States manufactured after 1966 got its red from this mountain. In 1994, when Mojave National Preserve was established, Clark Mountain was included within its boundaries.

This ideological narrative, formed during the colonial period, remains operative today in an economic context that propels us toward catastrophic global climate change under the inequities of racial capitalism. The rare earth frontier is the frontierism of our enduring neoliberal era, a time of increased police militarization, global surveillance, and increasingly extreme privatization and extraction. Though similar to the frontier mentality of the nineteenth century, the narrative now includes not only digital technology and weaponry but also an “end of-the-world” ideology that determines and sustains its form and method. It is distinctly post-9/11 in its particular paranoias and aspirations, yet it is also rooted in the visions of total surveillance from earlier epochs of American paranoia.

This projection of endless surveillance and war is a crucial component of what allows the supposed wasteland of the desert to be “recuperated” through continued investment. The Molycorp mine’s management had promised investors and local politicians that the minerals processed at Mountain Pass would facilitate the creation of equipment not only necessary for green technologies but also for the American military. But even though none of the rare earth elements for the manufacture of military equipment was actually in the ground at Mountain Pass, the “critical minerals” narrative worked long enough to raise millions of dollars in investments. In the Mojave Desert, the mining pits and shafts of the past centuries’ prospecting are scattered around the parklands and desert roads. Through the many eras of US history, mineral matter has been fundamental to the generation of power: social, ideological, militaristic, and energetic. With the incorporation of rare earth technologies, these powers course through the flicker of location services, data mines, and surveillance servers, through our screens as we watch ourselves and the state and its corporate affiliates find new ways to ensure their power by watching us back.

The Mountain Pass mine sits at the foot of Clark Mountain, which consists in part of rock more than a billion years old heaved up from deep beneath the earth’s surface as a result of the collision of the North American continent with the oceanic crust beneath the Pacific Ocean. The mountains and playas of this desert lay bare the planet’s elemental story—Earth’s four-billion-year-old creation visible in its seams, transitions, and uplifts of stone. And the landscape is abundant with minerals; limestone, basalt, granite, turquoise, zinc, tungsten, borax, lead, copper, silver, and gold are all present. The Indigenous peoples knew an overland route from the area around present-day Santa Fe to the Pacific Ocean that crossed through this part of the desert, but it eluded the Spanish until they learned of it from their Mojave guides. The survival of the Spanish missionaries and gold-seeking soldiers relied heavily on the knowledge that the Mojave, Serrano, Paiute, Chemehuevi, Hualapai, and Vanyume peoples shared with them. Gold was once mined beneath this mountain, as were copper, zinc, and lead when prices for those metals rose steeply during World War I. The US government classified this land as public land when it took control of it, but its later, industrial use was facilitated by provisions such as those in the 1872 General Mining Law, which were designed to encourage the expansionist programs of “manifest destiny” and the mining booms of the Gold Rush. These laws sanctioned the forcible and violent conversion of Native American lands into American territories, which was often achieved for the US government by proxy via the miners, homesteaders, and ranchers who raced west and tied their livelihoods to these contested lands. Often, though, before the miner or settler made it west, speculators had already laid claim to huge tracts of land, seizing it at cheap prices, often under different names, thereby skewing supply and demand and creating some of America’s first real-estate bubbles. In the 1940s, a Nevada prospector, inspired by a government newsreel entreating citizens to seek uranium, took his Geiger counter out to an area around the abandoned gold mine at Clark Mountain, where he located a radioactive vein. What the prospector found wasn’t uranium, but a deposit of radioactive host rock containing one or more of the seventeen rare earth elements. Shortly after the Molybdenum Corporation of America (later renamed Molycorp) opened a mine there in 1952, two rare earth elements were found: europium and yttrium, both of which are necessary to create a bright red phosphor used in color television cathode tubes. The mine’s management claimed that every color tv in the United States manufactured after 1966 got its red from this mountain. In 1994, when Mojave National Preserve was established, Clark Mountain was included within its boundaries.